|

A guide to self reliant living |

|||||||||||||||

|

6. Kerosene heaters and cookers

12.

Electrical; generators

Miles Stair's SURVIVAL

Miles Stair's

SURVIVAL |

Beekeeping

Beekeeping and gardening go hand in hand. Many garden plants need pollination to produce edible fruits, and virtually all of them need pollination to produce viable seeds. Orchards absolutely require pollination in the spring and early summer to produce edible apples, pears, cherries, etc.

It just so happens that the honeybee is the most efficient pollinator. In years past, we could take pollination for granted because there were many feral honeybee colonies which would do the job for free. In the late 1980's, tracheal mites and Varroa mites, Asian bee mites, were introduced into America by some idiot queen breeder from Florida when he snuck some Yugoslavian queens into the United States. He sold queens and 3 pound packages of bees to migratory beekeepers, those who move hives from the Southern states northward as the season progresses, making their living off the $25 to $45 per hive per crop pollination fees. They spread the mites nationwide, and by the early 1990's tracheal mites and Varroa mites were decimating honeybee colonies.

Those beekeepers who treated their hives with miticides (Apistan Strips for Varroa mites, canola oil or grease patties for tracheal mites) could keep the mites under control and keep most of their hives alive. Feral colonies, however, could not be treated, and they were virtually wiped out. Those gardeners who depended upon feral colonies to pollinate their gardens and orchards began to experience greatly diminished crops, and many had to start keeping a few colonies of honeybees just for their own pollination needs. The side benefit of honey production was a very nice bonus!

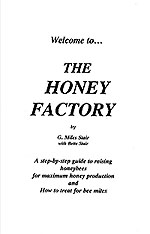

This article is not intended to be a complete, illustrated guide to beekeeping, but rather an incentive for those who need it to begin beekeeping. Thousands of books have been written on beekeeping - I wrote one myself - and no short article can begin to cover all aspects of beekeeping.

A normal beehive will average 40 to 45 pounds of surplus honey a year, according to reports dating back a century. You do not have to settle for "average" production, though. Ormand Aebi set a world record with 404 pounds of honey from one hive in one season, and I have no hope of achieving that production. Mr. Aebi lives in Santa Cruz, CA and has a eucalyptus tree nectar flow from January through June, whereas approximately 70 percent of our nectar flow (blackberry & clover) occurs in the 7 weeks between the first week in June and the 3rd week in July.

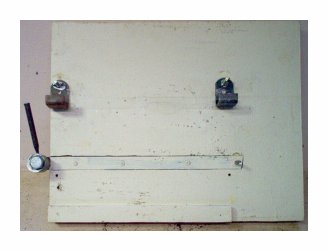

To obtain high honey yields, I had to invent methods to help the bees evaporate the nectar into honey more quickly, and I had to stimulate huge hive populations without inducing swarming, both of which I detail in my book. I also build elevated high stands (shown above) with a removable cover. The high stand cover sheds winter rain, the stand itself is placed over a black plastic sheet to eliminate ground moisture under the hives, and the stands are level side to side and have a 1/2" drop toward the front to keep the bottom board dry. The hive stand cover is in place from mid-August, when all honey supers must be removed and the hives treated for mites, and remains in place until honey supers are placed atop the hive in May. The average honey yield per hive is approximately 40 pounds because the bee colony tries to limit its population to about 45,000 individual bees. They can determine high hive population levels by detecting the level of carbon dioxide in the hive. When the bees feel the hive population is sufficient to gather their winter supply of honey for food, they swarm. What we must do is prevent swarming and artificially induce very high hive populations - up to 80,000 bees per hive. If a hive that large does swarm, there are still enough bees and brood left to bring in 100 to 150 pounds of honey. By drilling a 3/8" hole in the front of each hive body and honey super and providing an upper ventilation slot, air moves a little faster through the hive, displacing carbon dioxide and providing more evaporation for the nectar. With these modifications, hive populations can reach a critical mass of over 80,000 bees. The population of "housekeeping" bees remains about the same, so the extra bees are virtually all field bees, bring pollen and nectar back to the hive. That is why I have been able to average about 200 pounds of honey per hive per year for the past dozen years. You will have noticed that I used the word "usually" or "normally" in the paragraphs above. While we can manipulate hive populations, we have no control over the weather. If there is a summer drought, the nectar flow can dry up and reduce honey yields considerably, so testing various hive configurations and methods of working with honeybees can take up to a decade to determine the "average" results. Fortunately, it is easy to store honey for use in lean years.

Hive location is also critical. The hive entrance should face Southeast or South, with a good field of view in front of the hives. The hives do not need to be in the orchard or garden in order for them to do their pollination duties, but it is best to keep the hives within sight of a house if possible. I once had to place two hives out of sight of a house, and a bear really tore them apart. Swarms can be easily caught in bait hives. Old brood should be recycled by removing the outer two frames of each brood chamber in March, when they are usually empty of bees and honey. The frames are then spread apart, and two new frames with foundation placed in the middle. On such a cycle, the brood comb will be replaced every five years. That old brood comb is smelly and a very obvious attractant to bees, and can be used in a bait hive to catch swarms! Yes, a swarm will just fly right into the bait hive. Below is a photo of one swarm coming into a bait hive on June 19, 2004. All those white dots in the air are bees. Of course it is best to avoid swarms in your own hives through swarm control.

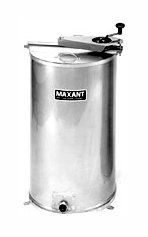

Remember, I have only given you a few high points on beekeeping. This is one hobby where planning ahead by extensive reading can really pay off. For example, working with beehives means lifting, so you will want to keep the weight of component parts under consideration before you purchase anything. A full "deep" super can easily weigh 90 pounds - at arms length - so while they work as hive bodies, deeps are not ideal for use as honey supers. A "western" or mid-depth super (6 5/8") weighs a little over 52 pounds when full of honey, yielding about 37 pounds of honey and having about 15 pounds of wood and wax. A "shallow" honey super weighs about 38 pounds when full, yielding approximately 26 pounds of honey. The type of centrifugal honey extractor you decide to use also is a factor here. My Maxant 3100 extractor will hold 6 frames of shallow supers but only 3 "western" or deep super frames. Obviously it is in my best interest to use shallow supers both for the lighter weight and the efficiency of extracting the honey with my extractor. Wooden frames must also be tightly wired, using a frame squeezer with an eccentric cam, to properly handle the centrifugal force of extracting and still last for decades of use. Plan ahead! Beehives can also be used in warfare!

|

|

|||||||||||||